7-2-22

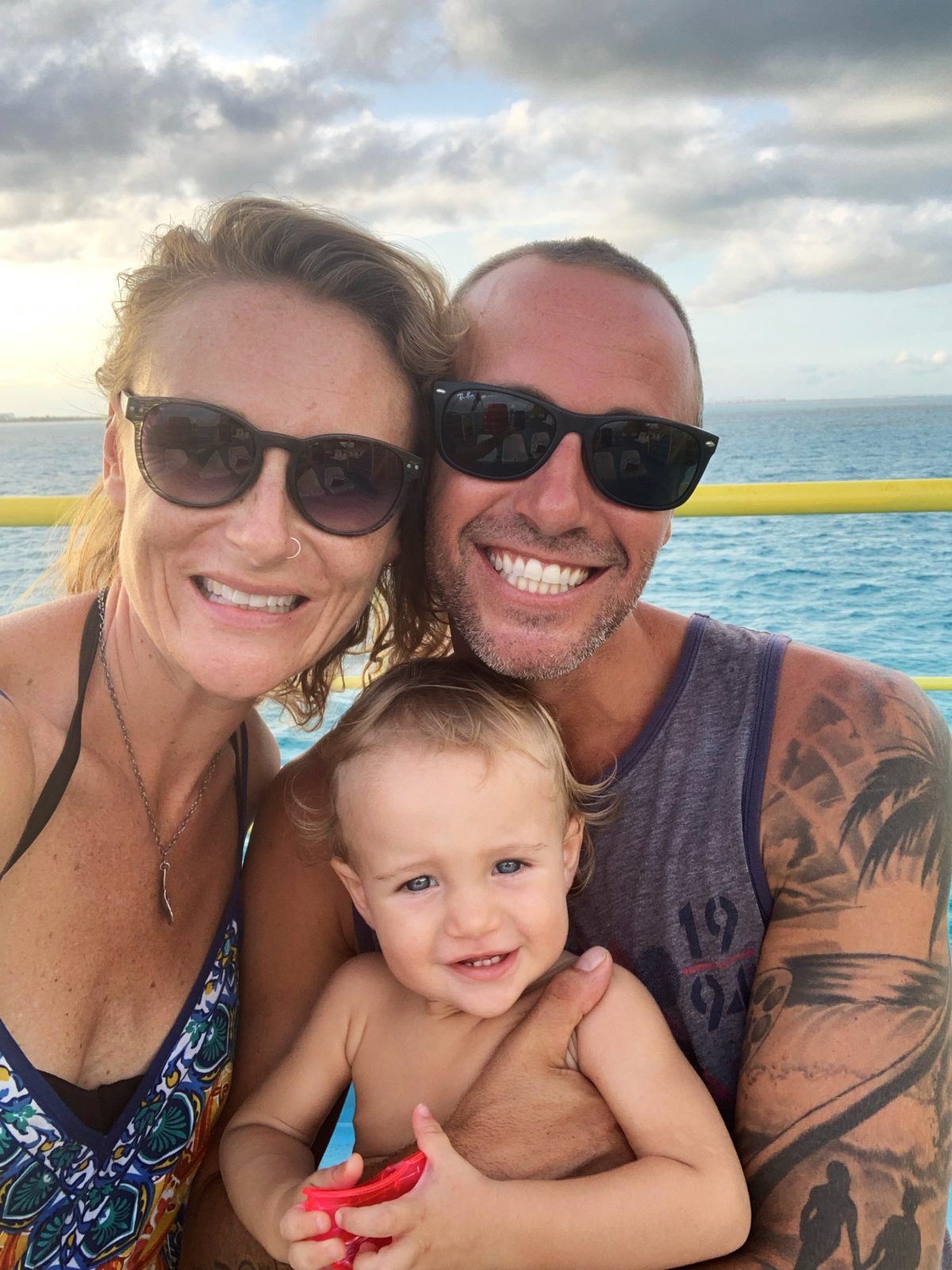

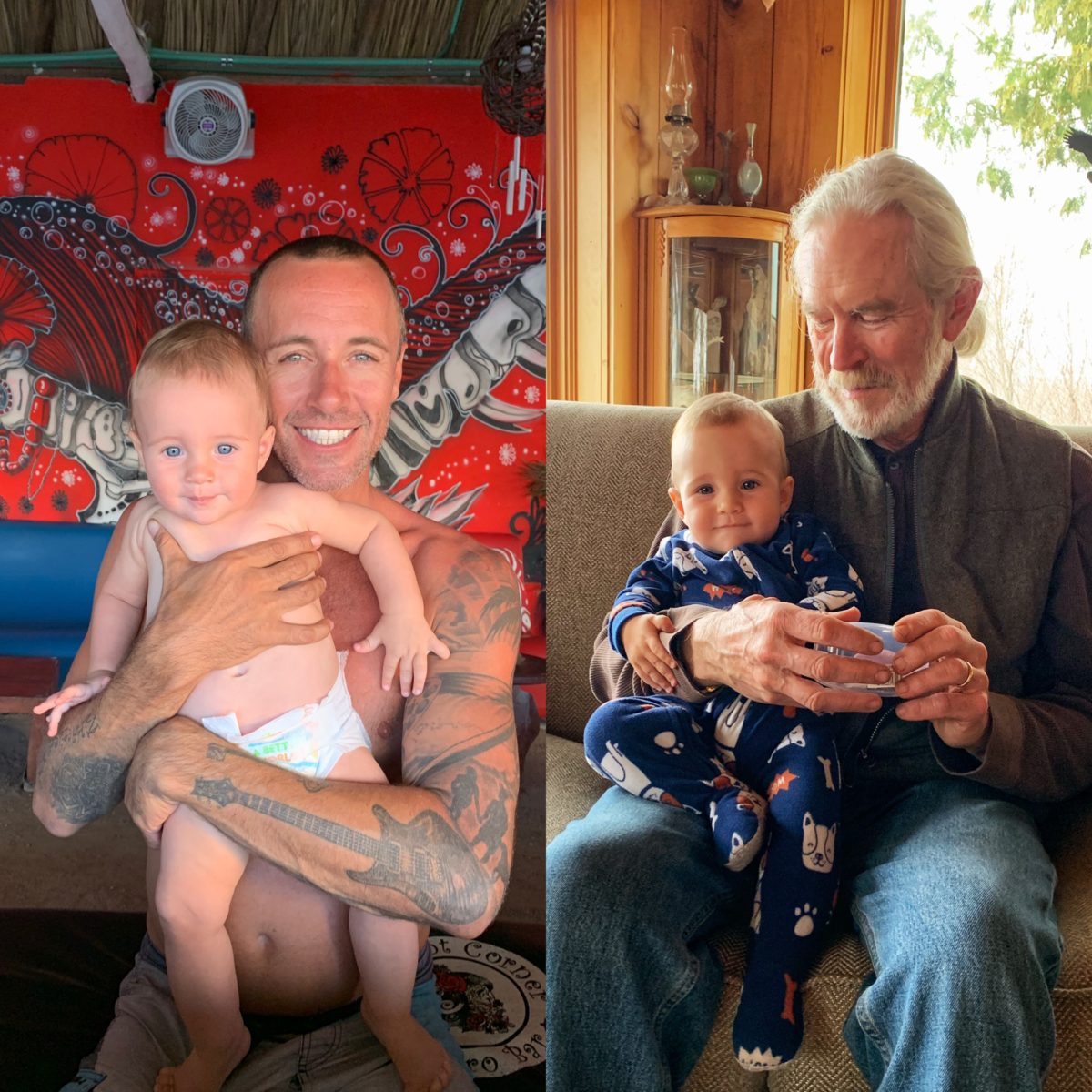

Watching my blonde-haired, blue-eyed, Mexican-born son as he effortlessly negotiates language, race, and class through play, I hold a sand dollar of hope in my cupped hands. Hope that children of the future like him will help change ingrained societal prejudices.

Where I was born, the natives were displaced decades ago, or assimilated into the largely Scandinavian population who inhabit Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

There were a few black children who came and went in our public school system, but other than that, diversity wasn’t something seen in the north woods.

For me, there will always be the unconscious/conscious notice of difference when it comes to race. It’s the framework in which I was raised.

I wish a different world for our son.

I sacrificed many things when I gave birth to Callan in Mexico.

My belly, split open like a ripe melon, our baby plucked from my womb, so he could be born in a new homeland. So that he might see the world through a different lens than his mother and father.

7-19-22

A note to my family; the smell of moss after an autumn rain in Michigan’s woods; the sigh of fresh water on rounded rocks; that particular gold of a northern Michigan summer evening.

I didn’t mean to leave you.

I have some adventures I need to see about.

Some things to do and see and experience

To help me

Make sense

Of this world.

7-27-22

Notes from The Coaster Amtrak train up the California Coast

All around me, a California divided.

Each train stop an encapsulation of how racial socio-economics segregate the United States. The beautiful coastal towns are white and blond. Affluence and skin color buy the best real estate. Homes with the best views. The best schools. Water. Healthcare.

On the outskirts—the margins—cling a motley group of middle class families. White, black, Asian, Hispanic. Their houses butt up to the tracks—a maze of neighborhoods on winding streets. Clinging to the edges of California’s nice neighborhoods as inflation grows, prices climb, gas goes through the roof, and there’s no parking for the cars necessary for jobs that barely hold down the rent-mortgage another month in a neighborhood that used to be affordable.

Those in the middle, slide down the economic scale every year as the wealthier grow richer.

I read an economic report today that said more people are spending only on necessities—nothing extra for their lives given in hard work.

64% of the United States lives paycheck to paycheck.

Juxtaposed against rising sales for luxury items.

Then there’s the rest of the population. The ones who’s numbers grow by the hour. In the same moments corporate offshore bank accounts funnel millions of dollars more than any one person or family will ever need, uncounted families disappear into poverty.

From the train I see homeless encampments—villages—small cities—where the folks who fell off the edges are allowed to make their homes because society doesn’t know what else to do with them.

The wealthy and homeless move around each other in this divided universe.

$500 shoes step carefully around sleeping bodies on the sidewalks.

The train moves away from coastal cities and suburbs. The landscape shifts to agriculture. A nation’s worth of strawberries grown and harvested by “migrant workers.” Men and women allowed to work the soil, but not to hold a place in society.

The train stops in cities named “Santa Maria” and “Santa Barbara.”

We disembark in a picturesque town edged in fields and vineyards full of brown-skinned workers. Cute downtown streets—boutiques, ice cream parlor, brewery, coffee shops—full of white patrons in hiking boots and Patagonia sweaters. A world away, from the reality on the margins.

8-25-22

I cannot follow a recipe

for anything.

It’s as though some part of me rebels at even

these

simple

rules.

9-15-22

I stand at my kitchen counter, cutting a fragrant, ripe, orange-fleshed papaya.

The sweet, milky aroma mingles with the tang of coffee and it’s pleasant, delicious.

Pounding wave sounds wash over a distant skill-saw whine, and occasional car horn.

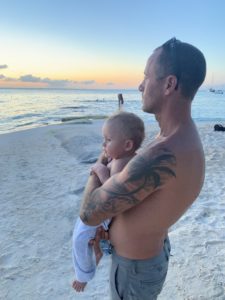

Pelicans glide above rolling ocean.

It’s a blue, enticing pacific today—personality swings and mood shifts mirrored in color changes and wave strength.

I take a deep breath.

Then another.

This is a lovely moment.

I would say, I’m happy.

But the last two years have taught me to feel leery of such moments.

Tempting fates I don’t believe in but that seem to tangle my threads every time a sense of contentment crosses my heart’s threshold.

Callan is in school. His first day at a new location just outside Tijuana where I hope with every fiber of my being he’s learning and growing from the experience.

He’s only four, but this is his third school and I ache for consistency—for our whole family.

He’s so damn beautiful in his signature sunglasses and flop of blond hair.

“I’m international baby!” Callan shouted when he plunked into his car seat this morning.

A line he heard on a show somewhere.

“What’s international?” He said after a pause, brow wrinkled.

“Well, a nation is a country. The US is a nation. Mexico is a nation. Being from multiple countries means you’re ‘international,’” I explained as I buckled him into his seatbelt.

“You’re international,” I say again, looking into his wide, earnest blue eyes. “You’re from Mexico and the US.”

“I am,” he says proudly, definitively.

9-16-22

Once you realize how subjective it all really is—that’s the moment of freedom.

There are no rules, really.

There is no guide.

Life really is what we make of it.

Choice.

How we fear choice.

The blessing and curse of being human.

Consciousness—we choose to see the world as it is, or we don’t.

Tipped scales against a horizon where the sun is always setting.

Tides, I learned, are a myth.

Really, the water bulges out as the earth turns. There is no rise and fall. No high and low.

Just an illusion we’ve built words and a romantic idea around.

9-18-22

Consciousness is a multi-faceted, sharp-edged jewel.

It makes it both possible, and impossible to fathom our own mortality.

My sweet, beautiful son, four years old, asks me why melons get moldy.

“It’s part of the cycle,” I tell him. “They’re returning to earth, where they came from.”

It makes sense in terms of a fruit, tree, or even animal, but is somehow impossible to contemplate our own place—or the place of the beautiful child before me—within the cycle.

Consciousness of our own mortality, or that of our children, is almost too much to bear.

Our awareness of rot, decomposition, is fearful and separate from our human bodies.

A thought only brought out in lurid books and media.

Relegated to the realm of darkness and the macabre, as opposed to a place within a larger cycle that cares not whether we are afraid, disgusted, in denial, or accepting of our place within it.

Regardless, our fragile animal bodies die and, if not disposed in another way, they decompose.

But why is this considered a dark, depressing thought to entertain, rather than perhaps a sense of satisfaction in fulfilling and completing our part in this glorious cycle we get to participate in as animals on this magical planet?

If not for consciousness.

It’s our own awareness, that makes peace of mind so hard.

10-9-22

I’ve lived in a diverse range of places: my lakeside family home; cabins in the woods; the old Nordic Bay Lodge hotel; dorms; a canvas wall tent for six months; a slew of camping spots and loaned beds and couches; three apartments on a tiny Mexican-Caribbean island and a home with a new baby and ten million mosquitoes; a lovely guest-house in affluent central California wine-country; a “hipster neighborhood” classic-cottage-style home in San Diego’s North Park with no screens on the windows and a bedroom the size of our queen size air mattress for $3000 a month; to our current brick edifice in Rosarito overlooking the cold, dirty, breathtaking waters of the far-north Baja coast.

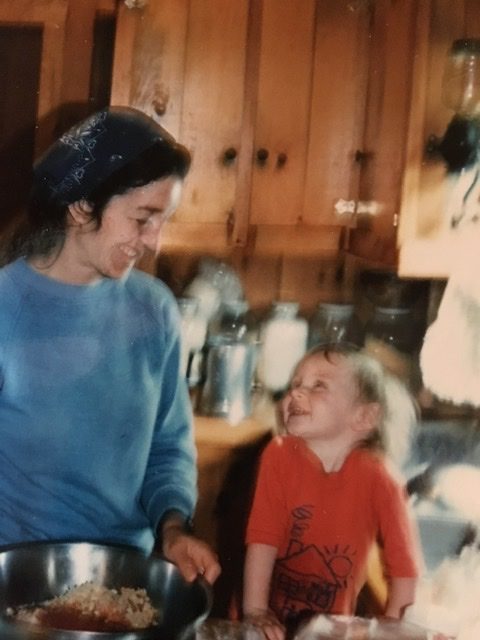

Before being a nomad, I lived my entire existence in the same house. On the same piece of land. Within the same water-centric world. I can conjure a moment in that place as easily as breathing. The way chickadees call from a tamarack tree on a frozen winter landscape. Where to find morel mushrooms in spring. The aroma of rain-wet maple leaves on a fall day.

What will our son remember?

Callan plucks a gone-to-seed dandelion, and then another.

He hands one to me.

“Make a wish momma.”

We take a deep breath and exhale together, releasing wishes and dandelion seeds into the wind.